- Home

- Adam Rothstein

Orthogonal Procedures Page 2

Orthogonal Procedures Read online

Page 2

The Assistant Secretary sat silently, enjoying the view of the memorials along the Tidal Basin as the car negotiated the track switches onto the George Washington Memorial Arterial, heading northwest along the Virginia side of the Potomac. Mackey could see where the angular plan of L'Enfant's District of Columbia still showed through the banked curves and whorls of the concrete tracks. Like translucent engineering vellum, the present-day capital of the United States lay overtop of the founders' Federal City.

Through this superimposed layer, traced with the humming pen strokes of bureaucrats' speeding electric P-cars, April sunlight managed to filter down to the historically maintained pedestrian blocks below, some still paved in nothing but lumpy cobblestone, the aggregate collection of the nation's history visible beneath its current state of the art machinery. From this side of the capital the towering federal skyscrapers were dark blocky masses caught in the silhouette of the morning sun, which gleamed bright even through the tinting of the car's rounded Perspex shell.

Downtown Washington DC was a range of architectural styles, the panoply collecting over the decades as new buildings were updated and added, torn down, and built taller. The singular impression was density. Rising levels of integrated office floor, stacked close together, drawing the various hives of government into close proximity with each other.

Or, at least a bifurcated proximity. South of the Mall was Federal Center, home of most central offices of the Department of Transportation. North of the Mall was the Commercial District, the location of many of the Department of Commerce buildings. For one instant, as the car shot north along the elevated, multi-lane track, he could see directly down the Mall past the Capitol, with these two halves of government neatly divided.

The radio broadcast transitioned into a musical interlude. A Bach concerto, played on an electronic synthesizer. As they rode amongst the congested midday traffic passing Arlington National Cemetery the P-car linked with several others in formation, coming to stasis at their rubberized pivot points at the nose and tail of the stainless steel tubular frame. The other cars, evidently heading in the same direction, made almost imperceptible contact as the radar systems brought them into close, inertially overlapping vectors. As the cars just barely did not touch, Hopper began to speak as if on cue.

"How much do you know about the history of the Department of Transportation?"

Mackey considered the question in the brief silence. Silence, except for the steady whir of the electric motors beneath the P-car, and the slight hiss of passing slipstream as they cut through the humid air of the capital area. One of the cars in the rear of their formation departed, taking the exit track to the Fairbanks Track Research Center, a facility of the Department of Transportation's Infrastructure Bureau. Mackey didn't know what he was expected to say to an executive of this stature, and decided to defer. "Certainly, I don't know as much about Transportation as you do."

Hopper rolled her eyes slightly behind the frames of her glasses across the span of the car from him. Mackey only just realized that although the P-cars could travel in either direction equally, she had managed to sit on the side of the car so that she would be facing forward, toward their destination, while he had his back to the direction of travel.

"This isn't a test, Mr. Mackey. I need to know what you know."

"I suppose I know the history of the Department as well as anyone my age. Plus, the requisite Level G knowledge about specific Departmental and Executive Branch protocols."

Hopper checked her wristwatch. Outside the window, the Potomac rolled on, a bit quicker now. The P-cars began to accelerate as traffic relented a bit through McLean. Out the window, Mackey could look down from the raised track and see the briefest glimpse of pedestrian malls, filled with early morning shoppers. Not individual people, just a blur of humanity visible from the speeding car. A mass of people, recognizable only by the space they were in. Hopper removed her glasses and began to polish them. The action alerted Mackey to a slight smudge on his own lenses, and he desperately wanted to clean his as well, but dared not do it at the same time as the Assistant Secretary.

"What," asked Hopper, leaving a noticeable pause, "do you know about Parallel Executive Procedures?"

Mackey took a glance out the window, reaching back into his Level G training for the definition. Nothing in bureaucracy was very complex—it just required a strong memory to recall the exact interpretations of the various terms and mechanisms, and the appropriate pathways between the myriad places on the organizational chart. "Parallel Procedures define the means by which different Executive Departments can pursue similar ends. To ensure no overlap of jurisdiction and to prevent waste and redundancy, each identical or symmetric activity must be specifically justified within the statutory mission of the Bureau, Service, or Department."

"If I wanted it by the book, I might have brought a copy." Hopper sighed and replaced her glasses. "Okay, Mr. Mackey, let's be frank. You are in the personal car of the Assistant Secretary for Innovation of the Department of Transportation. I could have built this P-car. I have, in fact, had it taken apart and put back together again, under my direct supervision, several times. There are no recording devices in this space. Your superiors and co-workers are not present. No one can hear you but me. Now what—" she leaned back into the patent leather, and gave him her friendly smile, "do you know about the relationship between the Department of Transportation and the Department of Commerce?"

Mackey could see plainly he wasn't answering the questions to her satisfaction, and so decided to play along.

"About as much as anyone, I suppose? I did well in Civics." He looked at Hopper, who was still waiting for him to respond, so he continued speaking. "Old rivalries die hard. And certainly, many people still have opinions about the pros and cons of one way of running a Department over the other. Commercialist versus Technocratic. Just on the radio this morning, I heard a political debate featuring a representative of each viewpoint. But those are just partisan politics. Part of the great American political tradition, stemming back to Jefferson and Madison."

He waited for her to ask him another question, but Hopper said nothing. Suddenly, the engineering elements of Mackey's mind began to take over, and he started assembling the pieces on his own. The Weather Service was one of the oldest agencies within the Department of Commerce. The Weather Service was the origin of Hopper's hacking event.

"Wait a minute." He spoke slowly as he fitted it together in his mind. "Are you saying that the Weather Service invaded—or hacked, if that's the term—Department of Transportation computers because of a decades-old inter-agency rivalry?"

Hopper said nothing, but continued to allow Mackey's brain to gnaw on the idea.

"But what good would Postal information about Department of Transportation employees be to the Weather Service, rivalry or not? If they were stealing data about some sort of project, or spying on some sort of Top Secret Postal research, that would perhaps make sense. Or if it was private industry, trying to glean for insight on staff and organization for lobbying purposes. But what would the Weather Service do with personal information?"

The P-car was cruising now, at speeds approaching two hundred miles an hour. They were well on their way to Reston, as Mackey saw from the information screen in the car console. Traffic had decreased enough that the car was no longer in formation with others, their unknown fellow travelers long since departed this track, continuing on their way to wherever they had been going. Mackey and Hopper rode along on their lonesome, or so it always felt to Mackey whenever he was traveling in an area uncrowded enough that there was no formation. P-cars were designed to form a chain if at all possible, to decrease air resistance and stress on the electric motors. Like the cars themselves desired the company, even if their human occupants did not. He continued pondering, now unable to drop the puzzle pieces he was fingering in his head.

"If the Weather Service was going to acces

s the experimental network at the Advanced Research Projects Bureau, wouldn't it make more sense for them to steal ARPB project information? It's an advanced project, information on the network itself might have been useful. Oh, except—" Mackey began to get it, "they already know all about the ARPNET, because they had to, in order to have hacked it. They already have their own Interface Message Processors, or they wouldn't have been able to connect at all. Otherwise they couldn't have requested or received the data packets. That means—" Hopper raised her eyes in anticipation of his P-car of thought arriving at the platform. "That means they have their own ARPNET, which they built under terms of Parallel Executive Procedures."

Hopper smiled, seemingly glad that her choice of personnel seemed to be working out.

Mackey's mind was not done yet. "But why," he asked, "did they use the ARPNET to access the Postal Bureau? Wouldn't they have had more access to Postal Bureau information via some other less experimental means?"

"We think they used the ARPNET because they figured we'd never suspect an intrusion into our own advanced, closed network. If we are the only ones who have the technology to form the network, how could there be anyone on it but us? However, they weren't counting on my engineers, who sleep with one eye on their mainframe clocks.

"As for why they want this information, we don't know. But it must have been important, because we didn't know about their ARPNET, or whatever they are calling their version, before they broke in. One of the cardinal rules of executive branch maneuvering is not to tip your hand. Work quietly, until the time is right. Whatever its use, the data must have been important enough for them to take a risk. They, like us now, must be on a deadline."

"But how could you not know about their ARPNET? Under the terms of the Parallel Procedures an inter-Departmental liaison must be established between the offices of the parallel Departmental Secretaries, or the offices of the redundant Bureau and Service Secretaries."

"This is why I need you. Not only are you an engineer, but you are an engineer who can clearly cut through the muddle of bureaucracy, to see what is really happening." The Assistant Secretary looked as blasé as her intensely sharpened personality could approximate. "Now—do you know what a Form 1286 is?"

He swallowed unconsciously, and took a moment to finally clean the smudge from his glasses. He knew exactly what the form was. "That's a form for receipt of materials classified Top Secret."

"That's right. And I'm not holding one, because I'm not giving you any materials. There are no written materials that relate to the Top Secret information I am about to tell you. And therefore, there will be no Form 1286.

"You may be surprised to learn that there are elements of our bureaucracy, Mackey, that are not written down. They are not committed to paper. I know quite a few. I am about to tell you about one of them. But believe me, despite its lack of paper trail, it is Top Secret. You know what happens when people fail to follow the procedures of a Form 1286. You might be able to guess that what happens when they fail to follow my unwritten procedures is fairly similar. Only there is significantly less paperwork to be filled out."

She made direct eye contact, and held it. Mackey returned her gaze while she spoke. "Parallel Procedures are justified by the statutory mission of the Department. When the very basic rationale for the Department's existence requires it, redundancy is allowed. There is nothing more crucial, nothing more important to any bureaucratic Department, than its statutory mission, its reason for existence.

"There comes a time when the statutory mission of this Department—our Department's entire reason for existence—takes precedence over the established procedures. In the same way that a Department might duplicate another's activities if its statutory basis requires it, our Department might abandon procedure if our statutory basis requires it. It's like a threat to life. When an animal's life is threatened, its behavior becomes extraordinary. Because if that animal fails to survive, it will exhibit no more behavior at all, ever again.

"Therefore, we must sometimes, so to speak, move at a tangent from procedure. And sometimes, that tangent will be not parallel to other Departments, but orthogonal. Just as there are times when we might duplicate the goals of other Departments, there comes a time when we must act directly against the goals of other Departments. These are known, secretly within the Department of Transportation, as Orthogonal Procedures."

As Hopper spoke, the P-car passed within sight of the terminal building of Dulles International Airport, switched tracks, and accelerated again as it continued west, on a lonely, straight track cutting across farm fields. The occasional P-car passed, heading in the opposite direction. Swishing past in a blink of an eye, the vehicles' combined relative speed topped 500 miles per hour. The buffeting slipstream sounded like a dull thud against the Perspex.

"The original, affectionately named ‘Pierstorff cars' were introduced by what was then the Post Office in 1916. Originally meant to deliver mail, the combination rail and road vehicles began to take on passengers. As any schoolchild can tell you, this was one of the most important technological events of the century, and our society has been built upon this foundation.

"By 1920, the Post Office plants manufacturing P-cars were some of the largest employers in the country. By 1924, the newly reorganized Postal Administration was more or less running the railroads with this new form of transportation, after the rail networks were left in shambles by the inbred, patrician monopolists who built them. In 1928, Roosevelt became Postmaster. Then followed the 1930s, and the heyday of the Administrations. Those were the days, my friend. You think you engineer things now, but you should have seen us! Things no one had ever dreamed of were flying off the drawing boards, out into the world." Behind the frames of the Assistant Secretary's glasses, Mackey could almost detect the faint presence of a gleam.

"We ran radio, we ran aeronautics, we ran the highways while we converted them to P-car tracks. Once we got radar in the thirties, we had the P-cars running themselves on the tracks, while we just ran the switchboards. Vail Labs invented us the transistor, and the switchboards became computers.

"In 1950, we got integrated circuits, and the computers were small enough to go in the P-cars. Everything in America was controlled by electric circuits. And the Administrations controlled anything with an electric circuit. Everything and anything that moved, from Alabama to Wyoming. We completed the national track arterial network in the early 1960s. Today, kids think a ‘road' is some sort of donkey path. We made that history, and we turned it into this present. There is not one part of this new world that we did not touch. The world we live in today was made by the Administrations out of whole cloth.

"A lot of people will tell you that the ideology of Technocratic Administrationism means this or that, whatever political soapbox of the month they can invent and broadcast on the airwaves. But there is one rule, Mackey, that overrides all other statutory jurisdictions, and bureaucratic procedure: don't let anything stand in the way of technological progress.

"That is our law. That is how Roosevelt won the war. That is what the national security of this country depends on. Without that one rule, that one idea behind everything that we do, this country blows its fuse. It no longer moves from Alabama to Wyoming, and it no longer moves between places much higher in the national priorities.

"It doesn't matter which Administration was responsible for what technology, it doesn't matter what Bureau you work for, or that the Secretary is a Cabinet man now. We follow our procedure. Whether that takes us parallel, tangential, or orthogonal to anyone else."

Mackey nodded. The Assistant Secretary was putting it in far harsher terms than how it was written in books or spoken on the news, but she was more or less right. The public trusted technology, and they trusted the Technocrats, or the Transportation bureaucrats, or whatever one wanted to call the people who ran the technology. The public trusted them, because the Technocrats' only responsibility was to

make the technology work. And as long as the technology worked, the Technocrats could do anything they wanted, and let Congress hold the hearings later. And, he reasoned, that could certainly include sabotaging other government agencies, if they believed there was a need.

"May I ask a question, Secretary Hopper?"

"Yes, Mr. Mackey."

"If Transportation has secret ‘Orthogonal Procedures,' and Commerce has Parallel Procedures to ours that include secretly duplicating the ARPNET technology—does that mean that we ought to suppose that they also have their own version of Orthogonal Procedures? A parallel of our Orthogonal Procedures? Some sort of protocol that they are secretly using against Transportation, in furtherance of what they believe their own statutory mission to be?"

"You're beginning to tune in the picture, Mr. Mackey."

Mackey looked at Hopper and tried to read just how big this puzzle was meant to be. The Assistant Secretary checked her watch again, then gazed out the Perspex at the farm fields, flipping past like the cells of a microfilm. When his co-workers spoke about Hopper's work as ‘a problem solver,' they either meant it literally in an engineering sense, or referring to her well-known clandestine service to the Administrations during World War Two. But surely, if she had worked with Postmaster Roosevelt, she must have been party to some of the episodes of his feud with the Secretary of Commerce. Not everything could be known to history. There were always conversations held in back rooms.

Mackey tried to imagine the Assistant Secretary in 1928, in her early twenties. That sharp attention to detail, the quick wit, the immaculate presentation and precise movements—all of these traits, forty-two years earlier, could have been deadly. Figuratively or literally. Had she been a spy? Or some other sort of shadow, black bag man? Black bag woman, that is.

He imagined her taking assignments from the Postmaster. What sort of task made up their strategy? Jockeying against Commerce and the War Department for access to President Landon, competing for wartime resources, poaching key technological personnel. Roosevelt had coordinated the technological projects of all the Administrations into a giant war machine. They had invented the cruise missile. They had invented electronic warfare. They had invented the atomic bomb.

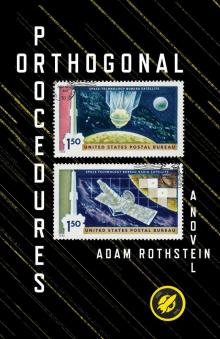

Orthogonal Procedures

Orthogonal Procedures